by Rocks Back Pages, Music Aficionada:: https://web.musicaficionado.com/main.html?utm_source=email&utm_campaign=WeeklyRecommendations#!/article/the_mothers_weird_journey_on_the_road_by_rocksbackpages

[ED: Originally Published in Zoo World, April 23, 1973 and Written by Arthur Levy].

| Courtesy of Getty Images |

The Mothers of Invention

If omens still mean anything in America, the good kind of omen, then it's time we all congratulated Frank Zappa for keeping the Mothers of Invention alive for the seven years since an album called Freak Out!

was first unleashed. And hope for at least another seven years of

whatever it is that Frank has been doing until now, which is, uh ...

weird, y'know?

"From there we went to Detroit and did a television

show there. There was no audience to see and we played at a roller rink

in some part of Detroit and the kids were still 1950s there.

"Then

we went to Dallas and worked in a shopping center at a place with a TV

show emanating from it. It was a sunken room with high windows that were

at street level so the people could look in and see a TV show going on.

And the kids were 1950s, still doing the dance where the legs go off to

the side," and Frank makes an upside-down "V" and wiggles the two

fingers to show how they danced.

"And I got back from that tour

and I couldn't even imagine what was going on around the rest of the

country 'cause I hadn't traveled that much prior to the tour. That was

Analysis number 1: I came up with the result of total mystification on

the part of all parties concerned. And it seemed that there was a

definite need, in the audience, for an alternative to what they'd been

presented with thus far in terms of music, entertainment, something to

do. It seemed like most of the kids we saw on that tour had already been

sold a complete bill of goods by everybody who was making novelties,

men's wear, women's wear, shoes. They'd gotten a kit and each area was

into its own little merchandising thing.

"Each tour after that I

would gather little bits of information on what the kids were doing,

what it was like to live in different parts of the country and up until

now I think the South is probably still the best in terms of just the

best attitude towards being alive."

If Frank's conversation seems a

bit unorthodox compared to what you know or have heard about him over

the years, it might be because he was talking over dinner in a Bavarian

restaurant not too far from a stage where he and the newest aggregate of

Mothers were to play a return to Florida, of sorts, a place that Zappa

had known well ever since he inaugurated Marshall Brevitz's Thee Image

(forerunner to Thee Experience, the rock hall whose name he took with

him to California when Jim Morrison shut out the lights on rock 'n roll

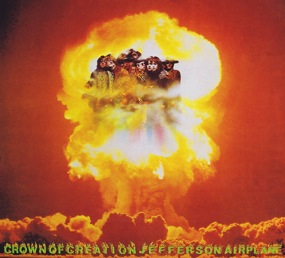

in Miami, March, 1969), warming up the club for bands like Led Zeppelin, Moby Grape, the Jefferson Airplane, Spirit, the Grateful Dead,

and a host of other bands that Marshall Brevitz brought to Miami

regularly in the heyday of 1968.

Now Frank Zappa sits in a Bavarian

restaurant surrounded by people who've long since forgotten about such

things and, frankly, hardly even notice the table with the twelve

musicians and hangers-on. Between bits of goulash and splaetzle (Frank

calls it "dumpling debris"; Steve the Roadie calls it "dumpling

leavings") Frank talks about Marshall in California.

"He's in Los

Angeles. My last two albums were recorded in his studio, Paramount. He

doesn't own it any more, though, it was changed over, sold out over

somebody's head.

"It was a good studio that's really good to work in but it's so

busy that they don't have adequate time to maintain the equipment. So

you take your chances. You go in there and a vital piece of equipment

might not work. So the engineer will call the maintenance man who'll

call Marshall who'll sort of show up with something to eat, you know,

while you're sitting there waiting for the machine to work. We've been

served barbecued dessicated chicken and hot dogs and many things. I had

so many equipment failures there that the next time it's gotta be

pheasant under chartreuse or I'm not coming back. Pathetic."

Business

is bizness with Frank, though, and any talk is inevitably going to

wander in the direction of Herb Cohen, Frank's legendary business

manager and dealer supremo who's had his say in everything from Wild Man Fischer and the GTO's to Alice Cooper, Tim Buckley, and Ruben and the Jets, the latest Bizarre spinoff.

"Herb's

doing fine, he's into architecture now. We just bought an office

building on Sunset Blvd. and we renovated it - what do I mean 'we' -

Herb designed some decorations for the building which are not exactly my

idea of a good time but he likes it and he's gotta work there.

"You

see, Herb, being a world traveler, has seen architecture of many lands.

And one of his favorites is the Moorish Arch. Only the Moorish Arch, in

all of its grandeur, has been translated into stucco by some guys he

found in Los Angeles. He says 'Open these windows here, a Moorish Arch,'

like that. And they say 'We can do it', so they bend a little tin and

put stucco around it and they're all different and all crooked.

"But

it has a courtyard in the middle of the office building and he can sit

in his office and look across and see two ugly Moorish Arches. That gets

him off, really, he loves it. There's a few other designs and factors

he's come up with. We've got an 11-foot hand-carved door in the front.

It was quite attractive for the first, I'd give it, 3 weeks. And then

suddenly the weather got to it. They must've put one coat of varnish on

it and already the parts are getting weird. So it's not Apple Records,

what the heck."

Apple should live so long. With the great

Southern and Western Expedition under full throttle (a Midwestern and

Eastern Expedition are slated for April or May; Japan, Australia, and

New Zealand are scheduled in June; and an invitation to the Iron Curtain

countries of Hungary, Poland, Czechoslovakia, and Yugoslavia is also

under consideration - all with this band) things are under a full head

of steam, with an awful lot of attention focused on young Jean-Luc Ponty, the French violinist Zappa has known but a short time.

"I

met him over here, he was working on some albums for World Pacific,

about 2 or 3 years ago. I got a phone call from Dick Bock, the producer,

who said he wanted to introduce him to me and I said 'sure' and he came

over to the house.

"I'd heard of him before but his English

wasn't as good then as it is now and so we couldn't talk very much at

that time. It was a little weird, heh heh. But his English is a lot

better now especially since he's seeing parts of the U.S. that a

European tourist might never go to. Learning about things like the

Waffle House, which is real big in Georgia."

The album that came

out of that initial meeting was called King Kong, a remarkable work when

you consider that budgetary limitations put studio time at a premium

and restricted several of Jean-Luc's solos to one take only. But now,

with Jean-Luc and Frank working together, things are more promising.

"We've

recorded some stuff already that's gonna be released. There's one piece

that I like very much, just he and I playing together. He's playing the

baritone violin and I'm playing the bouzouki, which, in case you don't

know, is a Greek, long-necked mandolin that I had tuned a funny way. And

we improvised a duet that's about 12 minutes - turned out really good.

I haven't named it yet but you'll know it when it comes out cause it

doesn't sound like anything you've ever heard before."

The band is

being recorded every night it plays - on one sixteen track machine

(just in case something of album quality should transpire), one

reel-to-reel stereo unit, and two cassette decks, which the band listens

to collectively on the bus or plane between dates. The cassettes are

the best learning device available, according to Frank, allowing the

musicians to adjust whole sections of the presentation if necessary,

relative to each other.

"Because of the instrumentation and because of the whole thing

being spread out across the stage, there's no one person in the band who

can hear all of the parts at any one time. You really can't tell – I

don't even trust my own judgment from what I hear onstage because I

don't have any perspective of it. I hear more of George's amp (George Duke, ex-Cannonball Adderley and Waka Jawaka keyboard man) cause it's right behind me and I can only guess what's going on in other parts of the stage.

"So

when everybody listens to a tape of it all have an equal shot at

tightening things up. I think it's a very practical way to do it and

it's all for the benefit of the audience 'cause they get a better

program out of it," which is spoken with the smiliest smile Frank has

smiled since the conversation began.

Once the band is to the point

where all the "musical technical" stuff is memorized it's time to work

on the choreography, always a vital part of any Mothers assemblage

onstage.

"It's structured up to this point: I say 'at this point

everybody will move', I won't say exactly what they're supposed to do.

One implication is that they're to twitch rhythmically at a certain

area, cause if you start saying '2 to the right, 2 to the left, back up'

and all that stuff, it's gonna look hokey. But just the idea that a

sudden burst of kinetic energy is released onstage at that musical

moment where it means something is very effective.

'"I think that

it tends to emphasize what the music is doing. The other main advantage

is that when you work in a hall that holds 10-15,000 people, anybody

who's halfway back in the hall sees you the size of a peanut. And if

you're standing absolutely still while you're playing the visual element

of the program suffers greatly and the person in the audience starts to

nod out. It's hard for them to retain a long interest span on inanimate

objects. But if you keep it moving a little bit ..."

Returning to the gig on the bus after dinner at Bavarian Delight, Frank mused into a song called 'Montana', a story song almost as outrageous as 'Billy the Mountain',

the mammoth production epic that was the highwater mark of Flo 'n

Eddie's tenure with Zappa. 'Montana' is considerably shorter than 'Billy

The Mountain' when performed onstage ('Billy' took 4 weeks to put

together and 6 months to perfect on-stage before it was recorded) with

an interesting story to it:

just to raise me up a crop of dental floss.

Raisin' it up, waxin' it down,

in a little plastic box I can sell uptown.

By myself I wouldn't have no boss,

but I'd be raisin' my lonely dental floss.

The last thing anyone ever mentions to Frank Zappa these days seems to be Flo 'n Eddie, ex-Turtles Mark Volman and Howard Kaylan, who've risen to the heels of success now, not quite a year since leaving Frank's company. While there are those of us who maintain that Flo 'n Eddie's disposition to Frank is considerably kinder and more good-natured than say, the attitudes of his ex-bass player Orejon (now back with Captain Beefheart, himself not the world's most fanatical Zappa-booster), Frank nevertheless maintains a strict attitude in their direction, especially concerning the hype Flo 'n Eddie disseminated to get some initial publicity when they left the Mothers.

"I was amazed that they could be so low-grade cause they were saying some outrageous lies and stuff just to get some kind of copy in the papers. View it as you wish, sensationalism, mere sensationalism."

Zappa and the band spent two and a half hours on-stage for their Florida audience and no one yelled out for 'Louie, Louie' even once. Or 'Caravan' with a drum solo, for that matter. Or 'Help, I'm A Rock'. Instead it was 'The Zombie Woof', you see, as Frank says: "A 'Zombie Wolf' would come from New England but a 'Zombie Woof' is interdenominational, he's Interfaith, you know what I mean? That's all I can tell you."